Why Are Motorcycle Makers Suddenly Going Automatic?

With BMW, Honda, KTM, Yamaha, Kawasaki, and now Ducati, looking at alternative transmissions, what’s actually going on?

Automatic gearboxes and motorcycles have never really seen eye to eye. Scooters, sure, but when it comes to big-cc bikes, riders almost always prefer to keep control of their clutches and shifts.

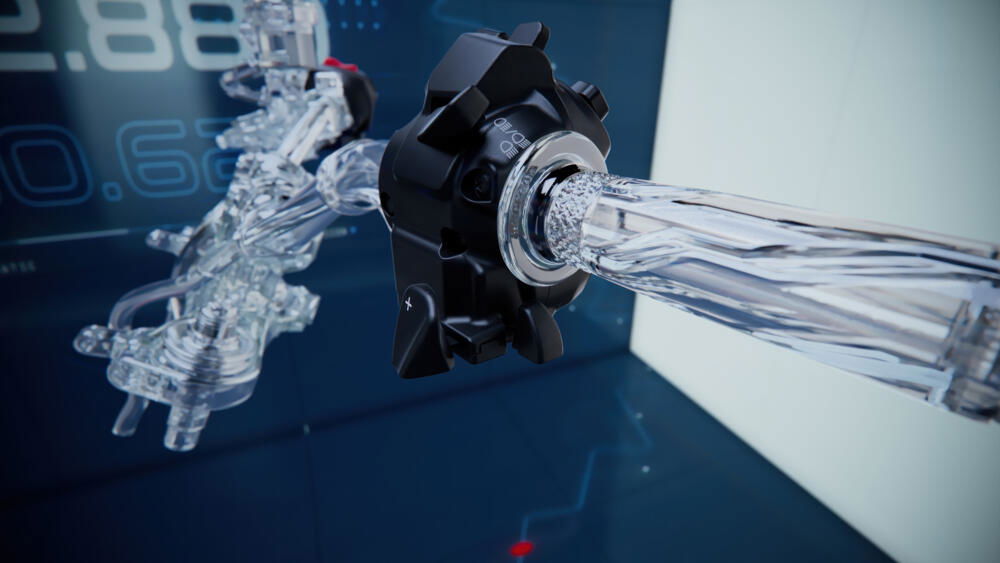

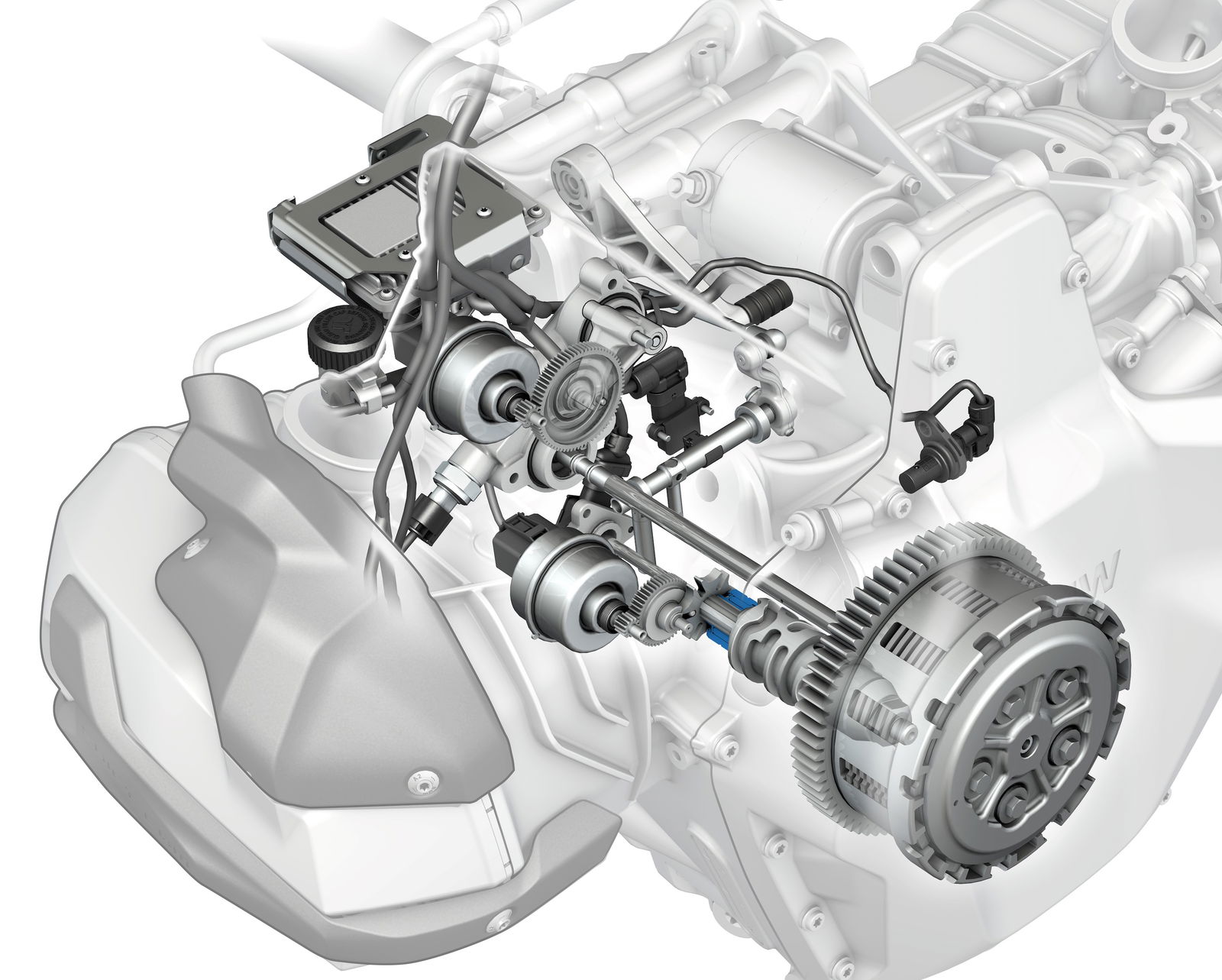

That's all changed in the last 18-months (or at least most bike makers think it has!) as in 2025 alone three major manufacturers are simultaneously introducing auto transmissions. Most prominent is BMW, which has announced ASA (Automated Shift Assistant) as a new option debuting on the R1300GS and GS Adventure, before it surely spreads to other models and engines. Next is KTM, with its AMT (Automatic Manual Transmission) gearbox was publicly demonstrated on a thinly disguised 1390 Super Adventure prototype competing at this year’s Erzbergrodeo. Most recently, Yamaha has shown some whizzy CGI renderings of Y-AMT (Yamaha Automated Manual Transmission), a system due “soon on multiple models”.

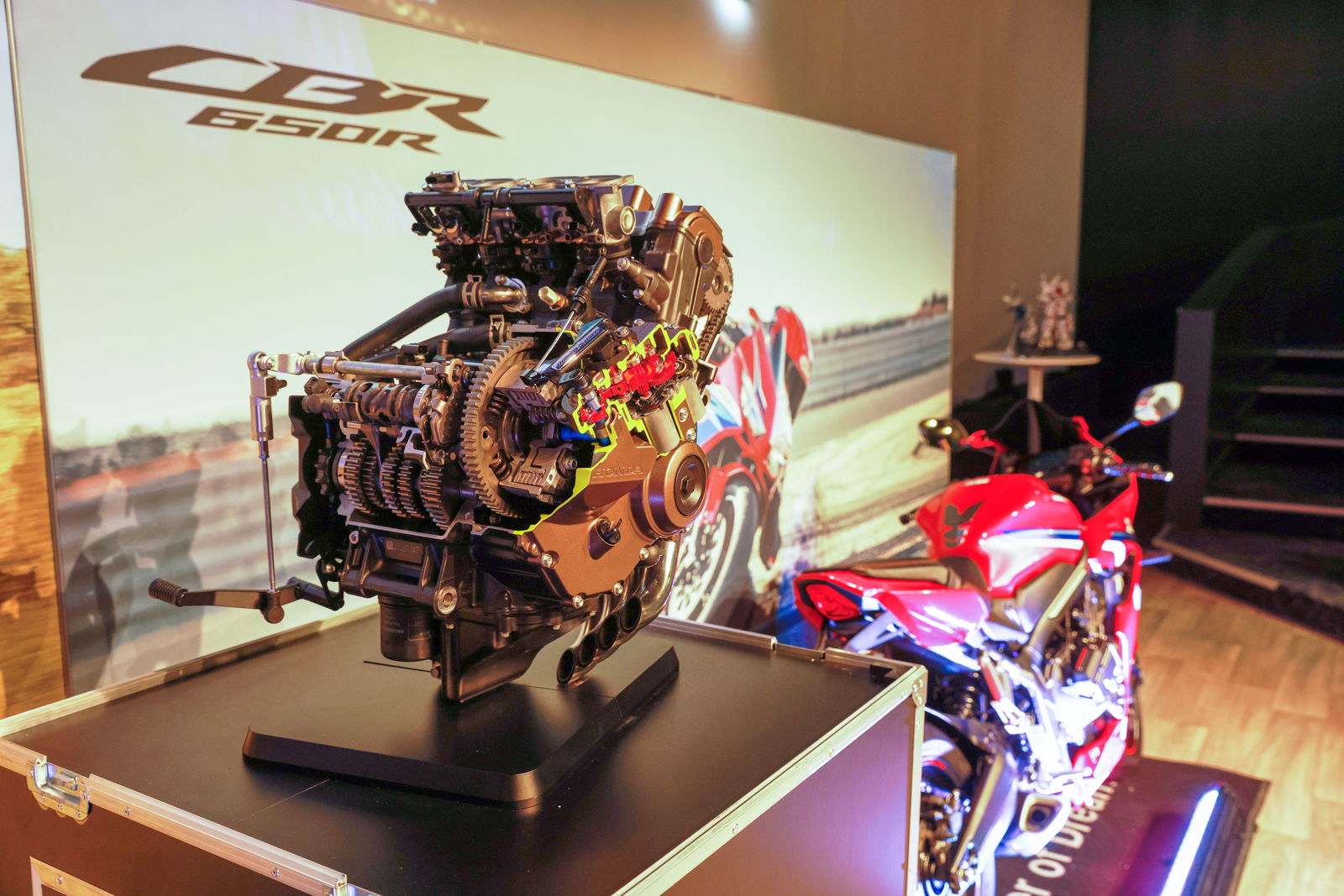

This trio will join the modest handful of advanced transmission systems on sale today. Kawasaki has already quietly introduced an electronic automated transmission on their Ninja 7 and Z7 Hybrid bikes. MV Agusta offers a mechanical Smart Clutch System (SCS) on their Turismo and Brutale 800s. Honda recently introduced the E-Clutch, a cheaper and simpler sibling to the Dual Clutch Transmission (DCT) it has offered since the 2010 VFR1200.

Snazzy shifting goes back even further. Before DCT was HFT: Human Friendly Transmission, a unique system found only on Honda’s brief-but-bonkers 2008 DN-01, which used pumps, swashplates and hydraulic pressure in place of a regular cogs-and-dogs gearbox. Two years before that was Yamaha Chip Controlled Shift (YCC-S), a push-button-to-shift transmission for the 2006 FJR1300AE. Carry on back to the 1970s and you’ll find Honda adding a torque converter to the CB750A ‘Hondamatic’. And before them all came the 1958 Super Cub C100, its Soichiro-specified centrifugal clutch famously designed specifically for noodle delivery riders.

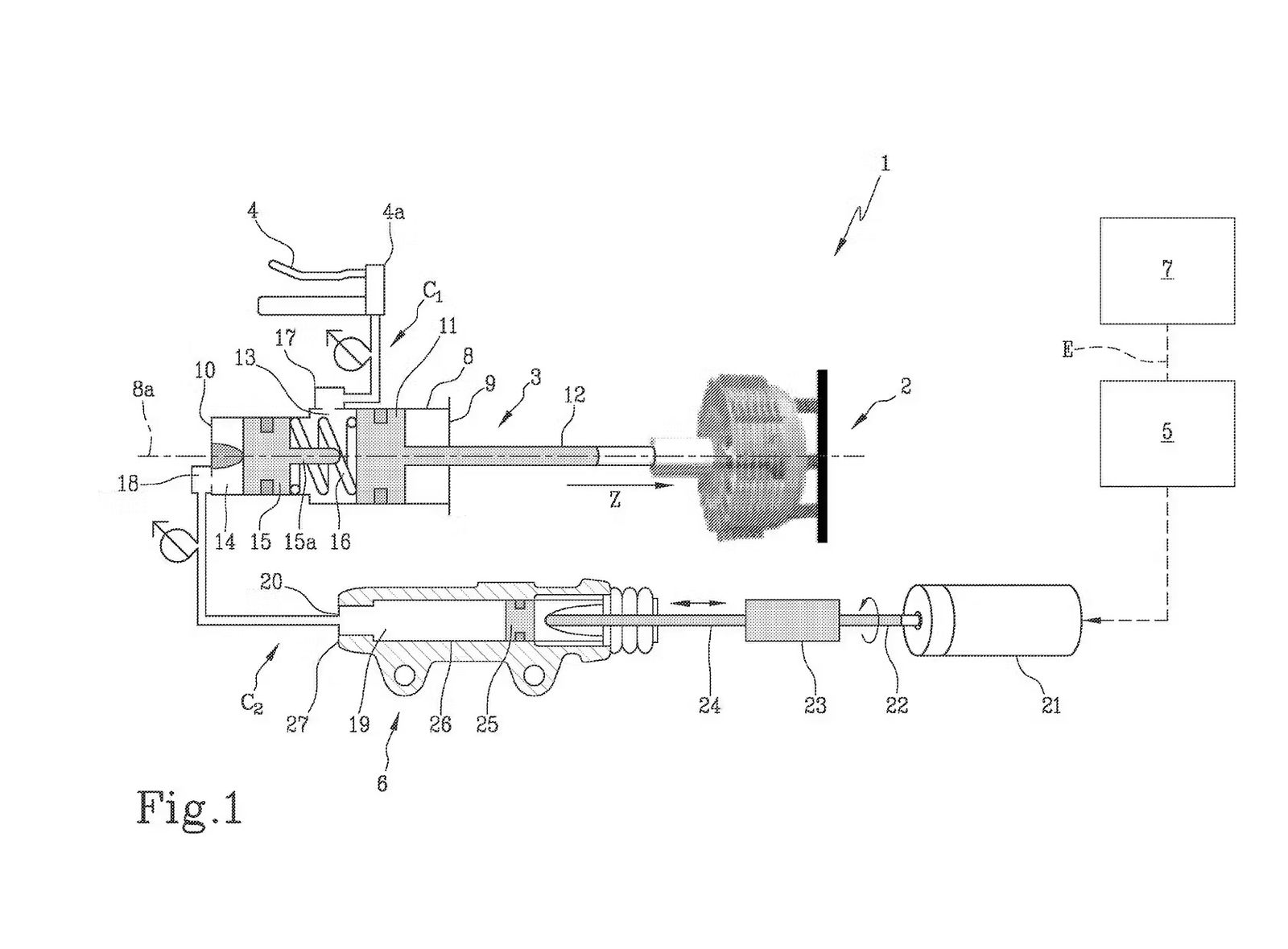

Ducati is the latest to hop on the bandwagon, with a system that is suprisingly simple for something coming from the Borgo Panigale. It's basically an auto clutch, or at least that's what the patent shows, and instead of a hand on the lever, you get a hydraulic actuator on a master cylinder. Importantly on the Ducati system - as its bikes are generally all about performance - the Italian system still seems to give the rider the chance to shift through the ratios in the conventional manner, making it a best of both worlds solution.

But while we’ll happily tar all of the above with the same “automatic” brush, the truth is these systems are hugely varied, each having control over different aspects of clutch and gearbox. To understand things better, we really need to break down “auto” into three defined areas:

- Clutch control (whether a system can control the clutch)

- Gearshift actuation (how gearshifts are carried out, either physically or electronically)

- Gearshift timing (when shifts happen, and whether the bike or rider decides)

Now we can start to draw some distinctions. Honda’s E-Clutch (above) and MV’s SCS both manage clutch engagement - (1) – but neither has any control over the gearbox. At best they’re auto-clutches, but it’s certainly not fair to call them automatic transmissions, nor to lump them in with everything else.

Yamaha’s original YCC-S controlled both clutch and gearshift mechanisms electronically (1 & 2), but it couldn’t change gear on its own – the rider always had to tell it when to shift. Honda’s DCT, however, is able to do all three, meaning it’s a true fully automatic transmission.

So where do these newcomers fit in? Conveniently, BMW’s ASA, KTM’s AMT and Yamaha’s Y-AMT all appear to share common traits. In all three systems clutch actuation is fully automated, leaving no lever on the left bar for a rider to operate or override. All three can change gears electronically, without the rider doing anything – so like DCT, they’re true full-auto setups. Like DCT all three also have a ‘manual’ mode, where the rider can choose when shifts happen, in the case of the BMW still using a foot lever rather than hand controls as on the other two.

That’s the how – but what about the why? Why is everyone jumping on the auto bandwagon now? The most obvious likelihood is that they want a slice of Honda’s DCT popularity. Since that first VFR1200 14 years ago, Honda has sold more than 240,000 DCT bikes across Europe. Last year in the UK, sales of the NT1100, CRF1100 and NC750X were split roughly down the middle: half DCT, half manual. Demand is definitely growing.

Some riders appreciate the reduced mental load, with less to concentrate on while riding, and fewer skills or experience required for newer or less confident riders. Some appreciate the reduced physical load, particularly those with mobility issues in wrists or ankles. Some appreciate the sublime, seamless smoothness of DCT’s gearshifts, especially those who carry pillions frequently.

There could be other factors at play beyond mere rider preference, of course. Letting a computer control clutch and gearshifts might make it easier for a manufacturer to meet future emissions standards, by timing shifts efficiently and removing human unpredictability. Perhaps firms could be following in Kawasaki’s footsteps, readying machines to integrate hybrid powertrains that tie together petrol and electric motors. Or perhaps bike manufacturers have simply seen which way the wind is blowing in the car world, where sales have swung strongly towards autos over manuals in recent years.

So does all of this spell the end of the clutch lever and the gear pedal as we know them? No: not anytime soon. These systems will, as far as we know, all be optional. They’re being introduced in addition to, not as a replacement for, regular traditional manual systems. And, contrary to some of the more madcap conspiracy theories out there, manufacturers aren’t yet able to force us to buy bikes we don’t want.

It’s down to manufacturers to design systems good enough to convince us as riders, and as riders, it’s down to us to vote for what we want with our wallets. If we buy them, they’ll build them. If we don’t, they won’t. The power to decide the future of automatic transmissions is, just like a traditional clutch lever, in our hands.