Road Test: Rockers Roll

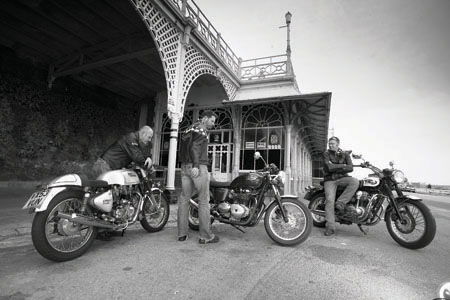

Reliving a past they never had on machinery they didn't own first time round, Alex, Jon and Jim indulge in a spot of nostalgic old school cool. Let's go retro...

|

Nothing is ever as simple as it once was, as obvious as it might have been or, indeed, there to clearly figure out in black and white. Some answers don't come easy, the questions only with a little less difficulty. Which leads us, in a crisp CGI-focused digital world to the first point to ponder: why, when everything on two wheels is getting faster, lighter and better, would you want a motorcycle that is antiquated, slow, heavy and quite plainly not brilliant?

Part of that answer we'll get to after a fashion. First a bit of history, which is what the Ace Cafe serves up as well as steaming mugs of tea and monumental fry-ups. The Ace is situated on what is now a bypassed backwater of a road that was once the arterial heart of London, the A406 North Circular. It was a transport cafŽ, and back in '50s and '60s Britain it existed to dish up tea and fry-ups to lorry drivers. It, and many like it, had a jukebox, which played rock 'n' roll records - a big deal at the time, because you couldn't get rock 'n' roll on the radio.

Teenagers invented themselves about then, horrifying the morass of grey-faced post-war adults - and teenagers wanted to listen to rock 'n' roll. And some of these teenagers also discovered that motorcycles, far from being poor man's transport, were actually exciting methods of getting around with a glamour and danger that added instant sex appeal. Obviously an important point, too. So heading to places like the Ace, listening to records, chewing the fat and simply hanging out with like-minded people became a way of life. The CafŽ Racer - the term, the man and the machine, was born.

It's a movement that's long since been relegated to the history books - the horrific death toll among the ton-up boys led to a tabloid war that thrust bikers into the public spotlight. Those that survived grew older and moved on, but while cafŽ racing (as a verb) has disappeared the bikes never really have. And here's the first irony - a cafŽ racer was actually a race-replica, mimicking the stripped down essence of the racers of the day by adding clip-on handlebars, rearset footpegs and engine tuning to standard machines. Rather than buying your race-replica you made your own, and as there weren't track days you raced it on the road.

So here we are, in 2004 with three motorcycles available to buy that look very much like they come from another time. One - the Triumph Thruxton 900 - is a cod reproduction of one of the original Triumph factory's racing bikes from 40 years ago. The first Triumph Thruxton was a hand-built racing legend, produced in limited numbers. Seeing one on the road then would be akin to seeing a Ducati 999 Corse running up to Saino's now. The Kawasaki W650, in yet another little twist of irony, is a more faithful visual copy of a '60s Brit Triumph than the Thruxton. Less ironic is the Enfield Bullet Sixty-5 Sportsman - built by Watsonian-Squire 30 miles from the original Royal Enfield plant in Redditch. Using components produced both in India and the UK, the Sixty-5 has perhaps the most direct connection with the past it purports to represent.

All three could easily be categorised in the 'old shite replica' bin of modern motorcycling but curiously, while they all might look the same, they individually dish up a very different experience. The fact they exist at all (ignoring the Enfield's lineage for a minute) is testament to the fact that sometimes simple is good and, while bikes are much faster, lighter and better now, boiling their component parts back down again and re-using an old recipe can work.

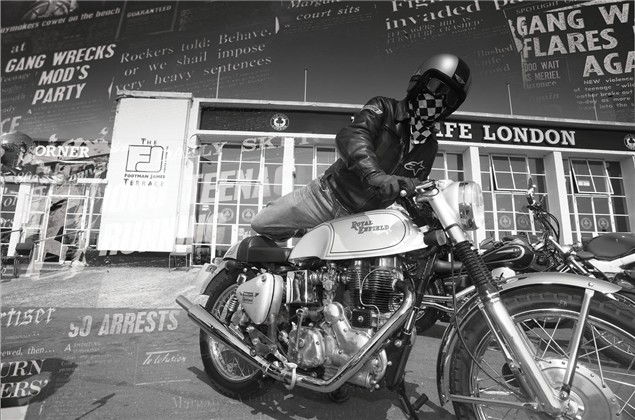

Taking them to the Ace Cafe, which re-opened in 2001 after a long sojourn as a tyre depot, was a little clichŽd, but also fitting, dealing as we are in post-retro-modernist-ironic-chic. As was running down the A23 to Brighton for a pint of Olde Foaming Fox Piss.

While the Ace has a ton of history riding on its tail it's also a good cafŽ. Good grub, good people and a crammed souvenir booth to satisfy punters' desire for a bit of Ace CafŽ to take away. We certainly did, and the hectic urban ride from south west to north west London was soon forgotten in a blur of egg and bacon butties, mugs of tea, bandanas, stickers and sew-on patches.

Motorcycling now is a leisure pursuit. Back when the Ace was packed with cafŽ racers for real, motorcycling was a more serious business. As we left its cosy portals, pockets and stomachs bulging, I wondered what the lads staring out of the mono-chrome pictures, with their black leather jackets, bare-boned bikes and bad attitudes, would make of us and our trio of faux-classic machines. Not a great deal, I reckoned.

That was then, this is now. And now for the three of us was London's suburban sprawl and snarling traffic. Which was okay, because these bikes make good town tools, particularly the twin-cylinder Thruxton with its skinny flanks and steeply raked clip-on bars. Urry, because he was a wearing a Triumph jacket and for some reason looked like he should be on it, was, and judging by the rodent-up-a-drainpipe way he was dispensing with queues was quite enjoying himself. Oh, and the big grin on his plug-ugly mush was a giveaway.

Jim, who more than anyone I know has been born out of time and should've been riding like a twat in the '60s, fitted the Sixty-5 like a glove. He didn't just look the part, he was the part. The only problem; like the rest of us he's used to modern levels of performance from engines, brakes and suspension, none of which his chosen tool offered. Did he care? Did he bollocks. He was basking in the racket from the Sixty-5's thumping great cylinder and and ignoring the fact that if he wanted to stop quickly he needed to give written warning to his front drum brake which, he reckoned after a near miss at a set of lights, "appears to have been knitted out of a combination of wool and rolled up milk bottle tops..."

I had the W650, not a bike you'll find in every Kawasaki dealer. Ours came from D&K, along with eccentricities added by a previous owner including an alarm, which ensured a constant flat battery. Fortunately the Kwak comes with a delightfully period kick-starter. With its high handlebars, rack and squashy seat it felt like a tourer. Its gentle, harmless twin-cylinder engine was nice and easy to get along with, but I had my work cut out to keep up with the others.

Urry without doubt had the 'performance' machine, with its 865cc engine and fettled suspension and brakes - all a major improvement over the standard Bonneville set-up. Jim on the wheezing, clanking, bellowing Sixty-5 had no such advantages, but did have the spirit of the cafŽ racers blessing him with extra speed and daring.

Rushing the W650 wasn't on. Where the Thruxton needs a good thrashing to make it come alive, the opposite is true of the Kwak. The W650 was best left to drift along of its own volition. Sit back, relax and watch the world slip by, with the odd stiff-edged salute to passing motorbicyclists.

But while these things are great around town, on the open road they ain't so bright. And while the M25 didn't exist 40 years ago, it certainly does now and we had to deal with it. The best bike, again, was the Thruxton. It's got the legs to keep up with 80mph motorway traffic, and a riding position to tuck into. I was strung out on the W650, aching to knock 20mph off my speed and settle back into that sweet 60mph zone the bike inhabits so well, while Jim had his chin under the paint of the Sixty-5's tank, hunting out every scrap of speed to stay with Urry. By the time we made the A23, our warm nostalgic glow had been ever-so-slightly frazzled by the frenetic pace.

We had to stop. Searching out another greasy spoon, more fried dead animal was the order of the moment. As the buzzing in our heads subsided and calm restored, the frenzy of the previous half-hour ebbed. By the time we saddled up and headed for the rolling South Downs, we were back in the mood for retro action.

And for the next hour, that was what we got. Plugging along, not desperately quick but fast enough to enjoy the ride and with the scenery rolling by, we wove our way south. We were, of course not riding this route for real - the cafŽ racing lunatics of yesterday would've, hell for leather, taking chances and risking all. Not us. If we want to get our adrenaline kicks now we'll ride a fast, competent bike on a nice safe racetrack in our highly protective clothing and helmet.

So the three of us just cruised to Brighton. And you know what? It wasn't half bad.

And roaring around Brighton's trendy streets was fun too, although not for the Sixty-5's clutch, which soon started playing up. But it was fun for us. People seemed to like the bikes and pointed, waved and stared. By now, we liked the bikes too, more so than we had previously. From the old-school cool of the Ace to the liberal funkiness of Brighton via the hell of the M25, we'd experienced something we hadn't before. Time for a pint.

We all had our views. Jim was convinced of Sixty-5's worth: "If I'm having a bike like this I want it to make a noise, be awkward, not have any brakes and be genuinely different to a modern bike. The Triumph looks the part from 20 feet away but when you get up close it's a low-resolution replica. The Sixty-5 is the real deal. It's slow, needs constant attention and doesn't do anything well. That's why I like it."

Urry wasn't convinced. He's a bloke in his twenties and, while he liked the Sixty-5's look, was more turned on by the Thruxton's performance. "You might as well buy a real classic bike as buy the Sixty-5," he reckoned. "For me the Thruxton has got the look just right and, more importantly, it works. What it's begging for is a set of loud pipes, but that's all. The engine's got enough grunt to make it fun and it handles, stops and steers well. I want the look without the classic bike experience and that's what the Thruxton gives. It's a modern motorcycle with enough style to make it different."

The W650 is the forgotten Kawasaki, but look hard at its handsome yet modern-feeling 675cc engine. The Thruxton outperforms it, but minus some charisma and - oh, yet more sweet irony - authenticity. At least Kawasaki were making twin-cylinder bikes like this sometime back then... even if they were copies of British bikes. Whatever. It's not a thrilling ride, it hasn't the primeval essence of the Sixty-5 or the crisp edge of the Thruxton, but it's got charm in its own unassuming way. But really, apart from its looks, knob-all else.

Why then, would you want a motorcycle that wasn't on the cutting edge of technology? The truth is you wouldn't. You just might want something different. Once, each of these bikes would've been absolute marvels, now they're eccentric sideshows. But that doesn't mean they don't have a place in modern motorcycling. The fact that bikes are so good now secures their place.

And it all boils down to this. If you want a real classic bike that'll leak oil, break down and underperform in every possible way, get the Sixty-5. It'll do all those things, but you'll form an empathetic bond of care and love. And it comes with a warranty.

If you want to buy a little piece of cafŽ race style without any of the hassle (or commitment, for that matter), the Thruxton's the bike for you. There's plenty of aftermarket bits available to make it the bike Triumph wanted to build but couldn't and somewhere a real motorcycle is begging to get out. Which leaves the W650. As everybody has, it would appear. If you want a gentle, classically styled brand new old bike this one's it. Kick start included.

SPECS - KAWASAKI

TYPE - STREETBIKE

PRODUCTION DATE - 2005

PRICE NEW - £5190

ENGINE CAPACITY - 675cc

POWER - 49.6bhp@7000rpm

TORQUE - 41.3lb.ft@5500rpm

WEIGHT - 195kg

SEAT HEIGHT - 800mm

FUEL CAPACITY - 15L

TOP SPEED - n/a

0-60 - n/a

TANK RANGE - N/A

SPECS - ROYAL ENFIELD

TYPE - STREETBIKE

PRODUCTION DATE - 2005

PRICE NEW - £4250

ENGINE CAPACITY - 499cc

POWER - 23bhp@5500rpm

TORQUE - 26lb.ft@5500

WEIGHT - 150kg

SEAT HEIGHT - 790mm

FUEL CAPACITY - 12L

TOP SPEED - n/a

0-60 - n/a

TANK RANGE - N/A

SPECS - TRIUMPH

TYPE - STREETBIKE

PRODUCTION DATE - 2005

PRICE NEW - £5999

ENGINE CAPACITY - 865cc

POWER - 58.6bhp@6900rpm

TORQUE - 48.4lb.ft@2800rpm

WEIGHT - 205kg

SEAT HEIGHT - 790mm

FUEL CAPACITY - 16L

TOP SPEED - N/A

0-60 - n/a

TANK RANGE - N/A

Nothing is ever as simple as it once was, as obvious as it might have been or, indeed, there to clearly figure out in black and white. Some answers don't come easy, the questions only with a little less difficulty. Which leads us, in a crisp CGI-focused digital world to the first point to ponder: why, when everything on two wheels is getting faster, lighter and better, would you want a motorcycle that is antiquated, slow, heavy and quite plainly not brilliant?

Part of that answer we'll get to after a fashion. First a bit of history, which is what the Ace Café serves up as well as steaming mugs of tea and monumental fry-ups. The Ace is situated on what is now a bypassed backwater of a road that was once the arterial heart of London, the A406 North Circular. It was a transport café, and back in '50s and '60s Britain it existed to dish up tea and fry-ups to lorry drivers. It, and many like it, had a jukebox, which played rock 'n' roll records - a big deal at the time, because you couldn't get rock 'n' roll on the radio.

Teenagers invented themselves about then, horrifying the morass of grey-faced post-war adults - and teenagers wanted to listen to rock 'n' roll. And some of these teenagers also discovered that motorcycles, far from being poor man's transport, were actually exciting methods of getting around with a glamour and danger that added instant sex appeal.

Obviously an important point, too. So heading to places like the Ace, listening to records, chewing the fat and simply hanging out with like-minded people became a way of life. The Café Racer - the term, the man and the machine, was born.

It's a movement that's long since been relegated to the history books - the horrific death toll among the ton-up boys led to a tabloid war that thrust bikers into the public spotlight. Those that survived grew older and moved on, but while café racing (as a verb) has disappeared the bikes never really have. And here's the first irony - a café racer was actually a race-replica, mimicking the stripped down essence of the racers of the day by adding clip-on handlebars, rearset footpegs and engine tuning to standard machines. Rather than buying your race-replica you made your own, and as there weren't track days you raced it on the road.

So here we are, with three motorcycles available to buy that look very much like they come from another time. One - the Triumph Thruxton 900 - is a cod reproduction of one of the original Triumph factory's racing bikes from 40 years ago. The first Triumph Thruxton was a hand-built racing legend, produced in limited numbers. Seeing one on the road then would be akin to seeing a Ducati 999 Corse running up to Saino's now. The Kawasaki W650, in yet another little twist of irony, is a more faithful visual copy of a '60s Brit Triumph than the Thruxton. Less ironic is the Enfield Bullet Sixty-5 Sportsman - built by Watsonian-Squire 30 miles from the original Royal Enfield plant in Redditch. Using components produced both in India and the UK, the Sixty-5 has perhaps the most direct connection with the past it purports to represent.

All three could easily be categorised in the 'old shite replica' bin of modern motorcycling but curiously, while they all might look the same, they individually dish up a very different experience. The fact they exist at all (ignoring the Enfield's lineage for a minute) is testament to the fact that sometimes simple is good and, while bikes are much faster, lighter and better now, boiling their component parts back down again and re-using an old recipe can work.