Triumph Tiger 900 T-Plane engine explained

Here's an in-depth look at Triumph's new T-plane crank engine, how it works and how it feels, on and off-road

.jpg?width=1600&aspect_ratio=16:9)

THE 2020 version of the Triumph Tiger 900 is the biggest change the model has seen since its reintroduction into the range in 800cc form.

In a search to make the bike more rugged and adventure-oriented, Triumph has developed a radical new engine they are calling the T-Plane engine. The idea is to create a Tiger with less tendency to spin and more inclination to dig in and go.

How does T-Plane crank in the Triumph Tiger 900 work?

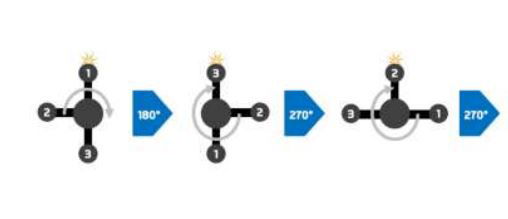

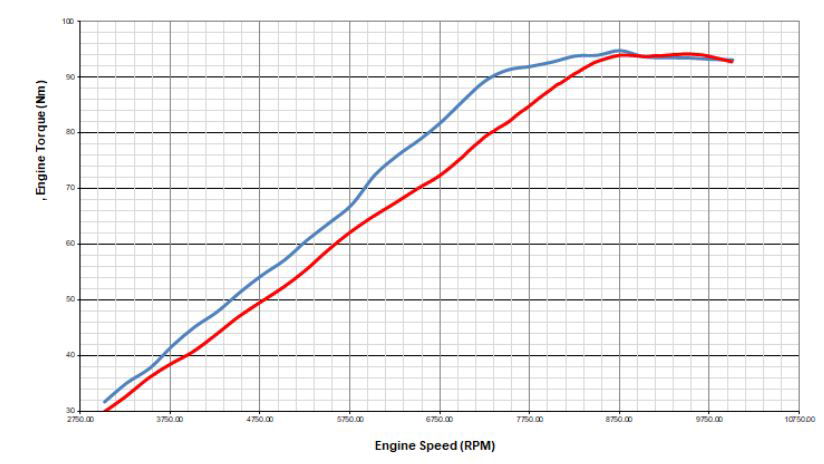

With the new bike putting out the same 94bhp as the previous 800cc Tiger, it’d be easy to surmise that the T-plane crank has failed as a new unit. More capacity equals more power, right? Wrong, the increase in capacity is more to do with preventing the new unit from losing out in the battle with Euro emissions regulations. Where this engine gets really clever is how it makes its power and torque, where it sits in the rev-range and, more importantly, how it’s delivered.

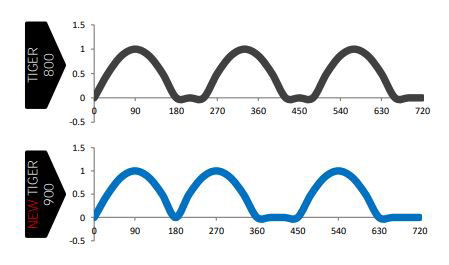

To get the desired result, Triumph chucked out the old engine’s architecture, which had the crankpins set at equal 120°. In that layout, the engine delivered a silky-smooth flow of torque, thanks to the equally spaced pulses from the engine.

Moving away from that, Triumph has installed the crankpins in the new engine at 0°, 90°, and 180°. This configuration combined with Triumph’s, 1,3,2, firing order gives the bike an uneven delivery, with two short gaps between the first two firing pules and then a long gap before the third arrives.

_0.jpg?width=1600)

On the launch of the new bike on the roads across Morocco, the new engine felt immediately torquier than the previous unit. But with 10% more mid-range on offer, that’d be expected. But the torque curve was only half the story. Riding on the road on day one I found the engine to have a split personality, which below 4,000rpm have the feel, delivery and almost the sound of a big V-twin. Above 4,000rpm the engine comes alive, reverting back to the feeling of a slightly vibey three-cylinder.

At this point, we’d done zero off-road riding. And to be honest, I could take or leave the new engine. Sure enough, the extra mid-range was nice, but the extra vibes that came with it didn’t seem to like a price worth paying. At the end of day one I remember reflecting that the vibes weren’t worse than any big adventure bike, it’s just that in this case, I was always comparing to the Tiger 800, which was as smooth as silk in comparison. By the end of day one and riding 150-miles on road, I’d learned all I needed about the engine; or so I thought.

.jpg?width=1600)

With day two came the riding day that we had all been waiting. A full day of riding trails, dunes and even on the beach on the new Tiger 900. I tried to put the previous day’s slog across North Africa behind me, we set off to the first photo stop – which turned out to be only a couple of miles from the hotel.

The Tiger 800 is the red trace, the new Tiger 900 is the blue trace

It must’ve taken me just a few hundred feet of riding on dirt for the new engine and that quirky layout to make sense. The T-plane is an engine built to plug mud.

Where the old generation Tiger 800 was all fizzy top-end and spinning the back wheel from pretty much any revs, the new engine and it’s off-beat character digs in, allowing the chunky Pirelli Scorpion Rally tyres find some traction in the soft sand.

The Tiger 800 is the red trace, the new Tiger 900 is the blue trace

And don’t think that this new engine means the Tiger has lost any of its tail-happy fondness. Get the revs up above 4,000rpm and with the traction control turned off it happily slide around like a dirty great enduro bike.

The two engines in one concept is a very clever trick and one that I don’t think any manufacturer has pulled off so convincingly before. If you were a fan of the old Tiger 800, give it a go, but do so with an open mind – This Tiger has a totally different temperament.

Sponsored By

Britain's No.1 Specialist Tools and Machinery Superstores

When it comes to buying tools and machinery, you need to know you're buying from specialists who know what they're talking about.

Machine Mart eat, sleep and breathe tools and machinery, and are constantly updating their range to give you the very best choice and value for money - all backed by expert advice from their friendly and knowledgeable staff. With superstores nationwide, a dedicated mail order department and a 24 hour website offering quality branded items at fiercely competitive prices, they should be your first choice for quality tools and equipment.

.JPG?width=1600)